The Weevil and the Fly

The Mexican Bromeliad Weevil

The Mexican bromeliad weevil (Metamasius callizona (Chevrolat)) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) is a bromeliad-eating weevil (Frank and Cave 2005). The weevil is a specialist herbivore of bromeliads and consumes only those plants in the family Bromeliaceae. In its native range (Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize), the weevil does not cause damage to its host bromeliad populations. But in Florida, where the weevil was discovered in 1989, the weevil is causing great damage to Florida's native bromeliads.

Adult Description

The adult Mexican bromeliad weevil is 1 - 1.5 cm (0.4 - 0.6 in) long, black, and has a stripe across its wings. The stripe may be red, yellow, or orange, or occasionally not present or minimally present. The weevil has elbowed antannae and the classic weevil snout.

Weevil Life History

The Mexican bromeliad weevil has 4 life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. After mating, an adult female will lay an egg in the leaf of a bromeliad (Salas and Frank 2001). About 8 days after the egg is oviposited (at 25 degrees C, 65% RH), a larva hatches from the egg and begins mining the leaf. Eventually, the weevil grows too large for the leaf and begins eating the stem of the plant. The larva eats and grows for about 5 weeks, then creates a pupal chamber from plant material and pupates. About 12 days later, an adult emerges from the pupal chamber and the cycle starts over.

Arrival and Spread of the Weevil in Florida

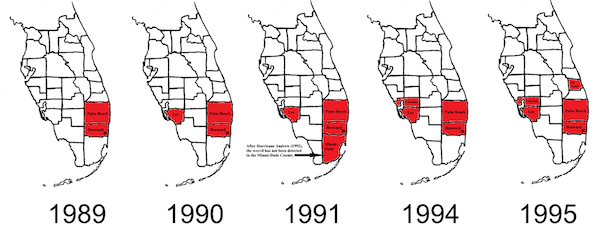

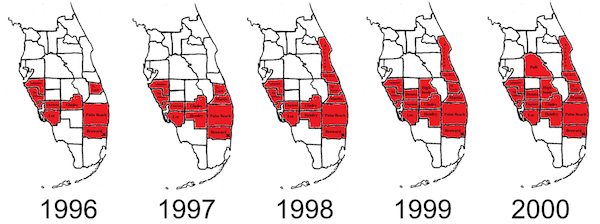

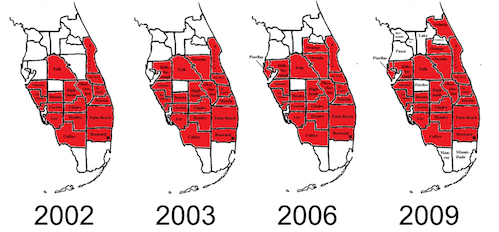

In 1989, inspectors from the Florida Department of Agriculture found weevils in bromeliads in a nursery in Ft. Lauderdale, Broward County (Frank and Cave 2005). Surveys in surrounding natural areas showed that the weevil was already established in native bromeliad populations and could not be eliminated (Frank and Thomas 1994). The weevils in the nursery were killed using chemicals, but it was too late to contain or kill the weevils that had escaped to the wild.

The 12 species of Florida's bromeliads that are attacked by the weevil range from central to south Florida. The bromeliads are restricted by cool weather; the range of the weevil is restricted by the range of the bromeliads (Cooper and Cave 2016).

Since 1989, the weevil has spread to nearly fill its new range (Frank 1996). Within the first year of its arrival, the weevil was found on the west coast of Florida, probably transported on infested bromeliads carried by humans. The weevil is capable of spreading on its own quite well, however.

The weevil is now in 22 counties. Those counties without weevil sightings (Hardee, Monroe, and Miami-Dade, where the weevil was found in a park in 1991 but, after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, was not found in the park) may be due to a lack of surveys.

The weevil is native to Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize and came to Florida on ornamental shipments of bromeliads. In 1992, Frank and Thomas (1994) traced the probable origin of those bromeliads to infested shade houses in the state of Veracruz, Mexico.

Weevil Damage on Bromeliads

Weevil larvae kill the plant by chewing the meristematic tissue (Frank and Thomas 1994). This action causes the core of the bromeliad to fall out of the plant to the forest floor. When the weevil first arrived in Florida, fallen bromeliad cores were found littering the floors of weevil infested forests.

The fallen core has a very distinctive look. The leaves are loosely held together and they have an "exploded" look. If you pick up the core, the base is without roots, and there are large, ragged chew marks on the bases of the leaves (made by the weevil larva).

Sometimes you will find a brown gelatinous substance that is thought to be a defensive response made by the plant (Frank and Thomas 1994). It does not protect the plant from the weevil.

The weevils have a preference for larger plants and even mine the inflorescence of reproducing plants (Frank and Thomas 1994, Cooper 2006), destroying seeds that are much needed to create the next generation of plants. The weevil is able to persist on smaller, younger plants.

Weevil specimens can often be found in freshly fallen bromeliad cores. In large bromeliads, several specimens of different life stages may be found in a single plant.

Franki Fly

A biological control program was started in 1991 to control the Mexican bromeliad weevil (Frank and Cave 2005). In 1993, a potential biological control agent, Franki fly (Lixadmontia franki), was discovered in Honduras on a related bromeliad-eating weevil, Metamasius quadrilineatus (Wood and Cave 2006). The fly is a specialist parasitoid of bromeliad-eating weevils.

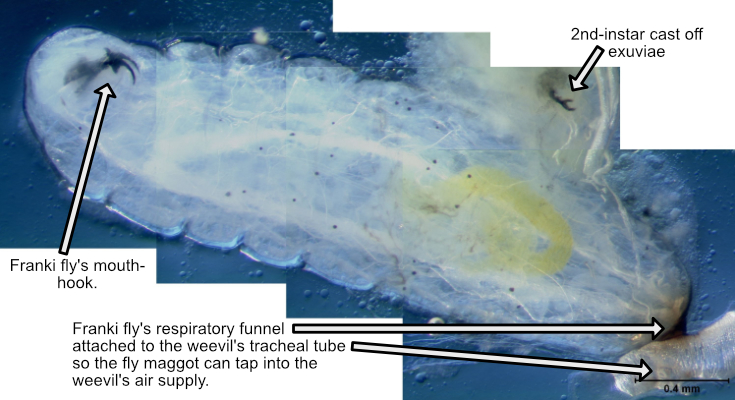

After mating and internal development of her eggs, an adult female fly deposits maggots on a weevil infested bromeliad (Suazo et al. 2008; Cooper 2009; Cooper and Frank 2014). The maggots go into the bromeliad and search for weevil larvae. When a maggot finds a weevil larva, it uses a sharp mouth hook to cut a hole in the weevil larva's skin. The fly maggot enters through the hole, into the body of the weevil larva. The maggot has a respiratory funnel at the posterior end of its body which it attaches to the weevil's tracheal tube, to tap into the weevil's air supply. The weevil larva remains alive while the maggot consumes the fluid in the body cavity of the weevil, carefully avoiding the internal organs. When the maggot is nearly full grown (third and final instar; see above image), it eats the weevil larva's internal organs, killing its host. The maggot emerges and pupates and the cycle starts over.

After many years of research and getting appropriate permits, flies were released in several natural areas in central and south Florida (Cooper et al. 2011). After each release, pineapple tops with 3rd-instar weevil larvae were placed in the release site about 5 weeks after a release. By this time, the adults that were released (the F1-generation) would, hopefully, have deposited maggots (F2-generation) on weevil-infested bromeliads, and those maggots would have emerged as adults, mated, and the females would be ready to deposit their maggots on weevil-infested bromeliads; hopefully, one of those females would deposit their maggots on our pineapple tops and the maggots would parasitize the sentinel weevil larvae. The pineapple tops were retrieved about 2 weeks after being placed in the field and returned to the laboratory, where they were monitored for parasitism by the fly. Only once were 2 flies recovered from a single weevil larva. After many years of releases, no other flies were caught in the wild and there were no signs of the fly having an affect on the weevil. Because Franki fly was so expensive and difficult to rear and because there was no evidence of success, resources were directed towards conservation efforts and alternative methods of controlling the weevil.

|