Save Florida's Bromeliads Conservation Project

PLEASE NOTE:

Tillandsia utriculata and several other of Florida's bromeliads are on

Florida's Endangered Species List and it is illegal

to handle them without permission.

At present, the Mexican bromeliad weevil is not contained in any way and is still destroying Florida's bromeliads.

This is a very short, non-detailed summary of Tillandsia utriculata conservation efforts. The most basic idea is to keep small, localized T. utriculata plants grown under protected conditions to maintain seed production in the hopes that one day the Mexican bromeliad weevil will be controlled, at which time the seeds could be used to restock forests—

BUT ONLY WITH PROPER PERMITS, PERMISSION, AND METHODS.

There are strict laws about where this conservation work can be done; you cannot just collect, manipulate, or release these plants anywhere you want to.

More information will be added to this page soon.

The Enchanted Forest Sanctuary (EFS) in Titusville, Florida once supported a very large, very dense population of the Florida native bromeliad Tillandsia utriculata. Sometime around 2006, an invasive bromeliad eating weevil (Metamasius callizona) arrived in EFS and started attacking the T. utriculata population. A study to monitor the rate of mortality of the medium to large T. utriculata caused by the weevil was done from March 2007 to June 2009 (Cooper et al. 2014). In the first 6 months of the study, 87% of the T. utriculata population was gone; at the end of the study, less than 3% of the population remained, and more than 99% of the deaths were caused by the weevil.

Alarmed by the rapid loss of the T. utriculata population and following the lack of success of the only known potential biological control agent to control the weevil, the Save Florida's Bromeliads Conservation Project (SFBCP) was started at EFS in 2015. The goal was to keep the T. utriculata plants alive while looking for an alternative method to control the weevil. Soon, other Natural Areas, Scientists, and volunteers became involved and started conserving their bromeliad populations.

Giant Airplant (Tillandsia utriculata) Life Stages

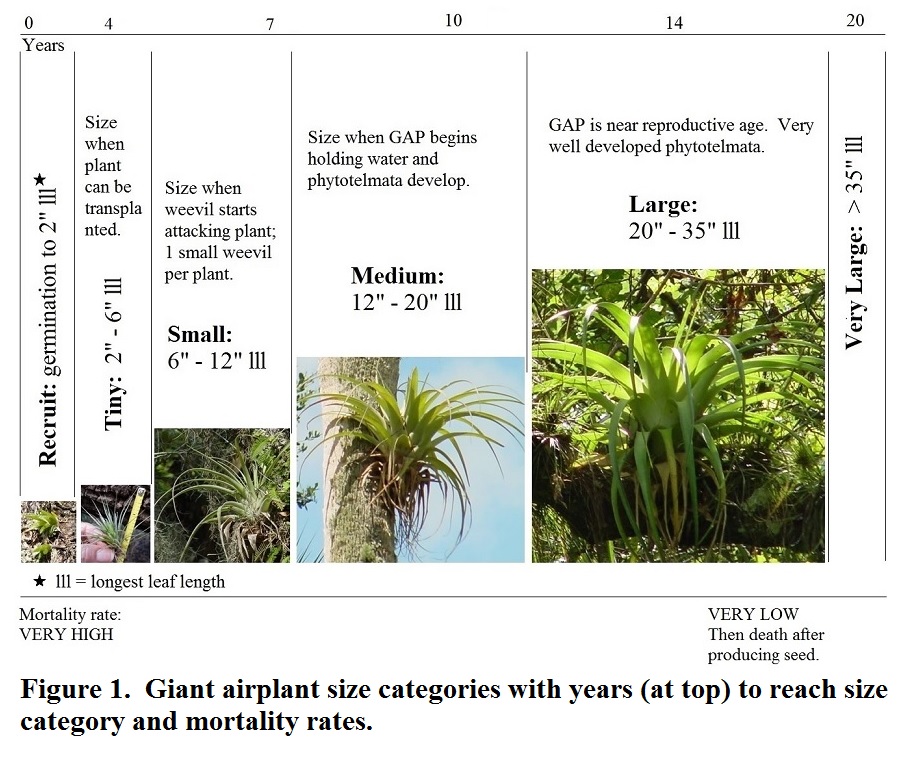

The giant airplant is a very slow growing plant that begins very small (leaves that are 0.1 to 0.08 inches (2 to 3 mm) in length) and finishes very large (leaves longer than 3 feet (1 meter) and with inflorescences over to 6 feet high (1.8 meters)). For this method, the giant airplant is divided into size categories. The sizes are based on the longest leaf length of the plant. This is a non-destructive way to measure giant airplants and estimations can be made even of those plants that are high in the canopy (Frank and Curtis 1981).

The numbers at the top of the above figure represent years of growth. It can take 5 to 7 years for a giant airplant to reach the size that can support a single weevil. It takes 10 to 20 years for a plant to reach reproductive age. Growing giant airplants from seed to mature plant requires a lot of time and space.

Giant airplant mortality is VERY HIGH when the plants are young (Benzing 1980, 2000). The mortality rate declines as the plants mature and becomes VERY LOW for large and very large giant airplants. A single giant airplant can release 10,000 seeds (Isley 1987). Those seeds ride on the wind and a small portion find a tree or vine or some other substrate to land on. Of those seeds, very few germinate. The recruit, tiny, and small giant airplants are very susceptible to changes in temperature and humidity and die from drying out or from rotting. These early stages also suffer mortality when branches break and vines fall down and trees slough bark or palms shed their boots and the bromeliads on these substrates fall to the ground and rot. The weevil does not attack these small plants because they are too small to support weevil larval growth (Cooper 2006). As a giant airplant moves from the small into the medium size category, it can support a single weevil larva, but plants at this size are not preferred by the weevil.

Those plants that found purchase on a strong, enduring substrate move into the medium size category and the natural mortality rate starts to decline (Benzing 1980, 2000). However, at this size, the plants become attractive to the weevil and a single plant can support 1 to a few weevil larvae (Cooper 2006). The larger the plants become, the more attractive they are to the weevil. The plants start holding water in their leaf axils and phytotelmata (plant-contained aquatic ecosystems) begin to form (Frank and Curtis 1981). Plants can put out an inflorescence at this size category, but this usually does not happen until the plant enters the large and very large size categories.

The large and very large giant airplants are near the reproductive age and are very attractive to the weevil (Cooper 2006). Mortality rate declines greatly (Benzing 1980, 2000). A giant airplant will put out an inflorescence in spring, flower, then seed pods form and the seeds develop over the year. The seeds are released the following spring and are viable for only a short time. During the process of seed production, the plant senesces and dies. The weevil can attack and kill a giant airplant even after the inflorescence has emerged and the seeds are being developed (Frank and Thomas 1994, Cooper 2006, 2009, Cooper et al. 2014). The weevil is so damaging to giant airplant populations because it is causing such a drastic reduction in seed production. If the giant airplant is extirpated in Florida, it will not be because the weevil ate the very last giant airplant, it will be because giant airplant seed output has fallen below a sustainable level.

Simply put, the objective of this conservation method is to maintain local giant airplant populations that are protected from the weevil. When the plants are young (recruits, tiny, and small) they do not need to be protected from the weevil but do need to be protected from dessication, rot, and herbivory or being ripped from their substrate. When the plants become medium size, they must be protected from the weevil. This can be done using a barrier such as a large cage, a greenhouse, a porch, or indoors; or using an insecticide. When the plants mature and produce seed, the seeds can be collected and used to propagate more plants to keep the population alive.

This is a method for conserving the plants to keep the species from diasppearing altogether. This is not a method to save the wild giant airplant populations or to restore the wild giant airplant populations to their former numbers and range. This is a method to keep localized populations of the giant airplant alive and producing seed until the Mexican bromeliad weevil can be contained.

And remember:

Tillandsia utriculata and several other of Florida's bromeliads are on

Florida's Endangered Species List and it is illegal

to handle them without permission.

If you are going to keep a giant airplant population alive and protected from the weevil, you can only legally do so on your own property and starting with giant airplants that are on your property. You cannot collect plants or seeds from other areas and take them to your property. You cannot take plants or seeds from your property and put them somewhere outside of your property.

|